Friday 29 September 2024

A wearable device that’s been designed to detect the onset of fatigue in tram drivers has delivered remarkable results in independent testing commissioned by UKTram.

The organisation representing the light rail sector reports that the cutting-edge technology, developed by Integrated Human Factors, has an accuracy rate of greater than 98%.

Following extensive trials, prototype FOCUS+ devices have demonstrated their potential to reduce the risk of accidents by alerting control room operators of possible driver fatigue.

James Hammett, Managing Director of UK Tram, expressed his confidence in the technology.

“The independent testing report confirms the potential of FOCUS+,” he said. “In the future, it could play a key role in fatigue management system guidance, ensuring the well-being and safety of network employees and their passengers.”

Trials of the device have emerged from an initial Driver Innovation Safety Challenge (DISC), which involved City of Edinburgh Council, Transport for Edinburgh, Edinburgh Trams, and the Scotland Can Do Fund, working in partnership with UKTram and IHF Limited.

Neil Clark, CEO of IHF Limited, explained: “We were proud to have been selected to develop this cutting-edge wearable technology as part of the DISC project.

“FOCUS+ was three years in the making, having evolved using a combination of data analytics, biometrics and Human Factors-best practice approach to safety.

“It represents a significant leap forward in proactive fatigue monitoring and workplace safety. I am excited that we have had the system endorsed by the LRSSB and can now go on and fully commercialise the system. We have already had inquiries from as far away as Australia, with its versatility making it a consideration for many hazardous sectors.”

A pilot, which started in 2020, collected a large quantity of data from its volunteers that was used to refine the product and to ‘train’ the FOCUS+ algorithms through machine learning. FOCUS+ then underwent rigorous testing and user-centric design enhancements in collaboration with UK tram drivers, control room personnel, data scientists, and independent volunteers.

The Light Rail Safety and Standards Board has also played a key role in the project, assessing algorithms that underpin the system.

Carl Williams, the organisation’s Chief Executive, said: “To establish the 98 per cent accuracy of the algorithms used to assess the data is certainly a remarkable achievement.

“It clearly illustrates the potential of the devices and the underlying software to effectively detect driver fatigue in real-world situations and to further enhance light rail safety.”

The prototype devices feature a sophisticated array of five biometric sensors that continuously monitor the wearer’s vital signs, creating a personalised biometric profile over time. These sensors measure heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, skin temperature temperature, electrocardiogram, and galvanic skin response.

Such comprehensive data collection enables the device to detect deviations from the wearer’s baseline, providing real-time, colour-coded alerts for both the user and a control room or supervisor.

Neil Clark added: “The ground-breaking solution has the potential to revolutionise fatigue detection in safety-critical roles across various industries. While initially tested by light-rail drivers, FOCUS+ has cross-industry applicability and is suitable for anyone in safety-critical roles across various organisations and industrial sectors.”

FOCUS+ is set to reshape the landscape of safety-critical roles, offering a proactive approach to fatigue prevention and management. To learn more about FOCUS+ and its capabilities, click here.

March 2024

Neil Clark, Melanie Mertesdorf and Sadaf Bader from Integrated Human Factors won this year’s CIEHF Innovation Award. They demonstrated outstanding human factors work in developing a game-changing, next-generation wearable device that proactively predicts human fatigue in its wearers.

Integrated Human Factors (IHF) have successfully developed a next-generation wearable device (now called Baseline NC) that proactively predicts fatigue in its wearers. The journey to create this device was filled with challenges and learning experiences. It required us to push the boundaries of technology and reimagine the way we address health, wellness, and fatigue prediction. Our team’s relentless focus on innovation, technology and just “getting it right” has led to a solution that is not just effective, but also user-friendly and accessible.

This device is more than just a wearable; we genuinely believe it to be a game-changer in fatigue management. Our initial focus is on trams and light railways however, the applications are pan-industry including the wider passenger and freight rail industries. By proactively predicting fatigue through biomarkers, IHF aim to enhance the safety and quality of life for many by providing a tool for data-driven fatigue management. It’s a step towards a future where technology and human performance merge seamlessly to empower individuals and improve overall system performance.

A pilot, which started in 2020, collected a large quantity of data from its volunteers that was used to refine the product and to ‘train’ the wearable algorithms through machine learning. The wearable then underwent rigorous testing and user-centric design enhancements in collaboration with UK tram drivers, control room personnel, data scientists, and independent volunteers.

The project was born out of a need to research, create, develop, and manufacture a viable unobtrusive product that could house a system whose functionality could accurately monitor, and alert increases in cognitive fatigue levels. As a workplace Human Factor Consultancy group, we recognised the need to ensure individual fatigue thresholds are never exceeded and suitable safety margins and processes are put in place to prevent or minimise the introduction of human error, which is often attributed to impeded arousal levels.

The devices feature a sophisticated array of five biometric sensors that continuously monitor the wearer’s vital signs, creating a personalised biometric profile over time. These sensors measure heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, skin temperature, electrocardiogram, and galvanic skin response. Such comprehensive data collection enables the device to detect deviations from the wearer’s baseline, providing real-time, colour-coded alerts for both the user and a control room or supervisor.

The project followed a system Verification and Validation (VnV) development and evaluation process. The evaluation of the Baseline wearable device was non-gender specific and was conducted via a combination of verified and validated subjective SART and KSS feedback, plus objective PVT assessments, in conjunction with observational data gathering from a non-interacting Human Factor Subject Matter Expert observer during simulated scenarios. The outcomes were compared against baseline recorded data and associated RAG status to see if indicated fatigue levels correlated. Independent testing showed that the wearable has an accuracy rate of greater than 98%.

September 2023

Ryan Donald is a Chartered Safety Professional (CMIOSH) and Human Factors Consultant (Chartership pending) with extensive experience in the management of safety in the subsea industry and experience in applying Human Factors methods in the offshore Oil & Gas industry. He has a master’s degree in Behaviour Change with a specialist pathway in Ergonomics and Human Factors.

How did you get into the Human Factors sector?

I used to be a Health and Safety Advisor in the diving industry and the organisation was keen on implementing behaviour-based safety approaches, focusing on intervention and safety conversations to increase occurrences of safe behaviours. Although this is important, I felt there was something missing from the approach. My first thought was “if we think behaviours cause incidents, then doesn’t it make sense to address the things influencing undesired behaviours”? Around about this time, a client was venturing into Human Factors and requested it be considered within our risk assessments. This was the spark that led me to pursuing a career in Human Factors, so I began studying. I soon realised it was a massively diverse discipline, one which considers the wider influences on behaviour and looks past “human error” to understand the true causes of incidents. Most importantly, Human Factors proactively evaluates influences on performance. I was, and still am, hooked so working at IHF gives me the chance to refine my skills further …

You mentioned the impact of the working environment on people. Can the working environment be that impactful?

Yes. In my opinion, the external working environment is one of the major influences on our behaviour. Take a competent person, add in a little work pressure and/or a poorly designed system, then you may have an increased the risk of error. When we think of a workplace we really enjoy being in, we may have high levels of intrinsic motivation. If we are challenged, developed and are left to our devices in terms of autonomy, then we may have stronger motivation. Take me for example, if I am micro-managed (with low autonomy), this effects my performance, especially my confidence and decision-making ability. This is an influence of my work environment and shows how the behaviour of others is an external influence on my own behaviour and subsequent performance.

What is your expertise and why do you like this part of your job?

I feel like I have a good understanding of what can influence us as people. I have a good understanding of cognitive process such as attention, decision making and memory in order to understand the influence of poor task / work environment design. I don’t think this is massively different from many Human Factors practitioners, but I pride myself in what I can bring to the role of a Human Factors Consultant. I really do feel in my element when doing human error analysis, really understanding a task and how it can influence the workforce psychologically as well as physically.

What do you like about working at IHF?

I really like the people, it sounds cliché, but they are a great bunch of people. Also, my role at IHF is very diverse. From safety critical task analysis, to applying research methods to explore experiences of the workforce to inform improvement initiatives. IHF have a wide client base across many industries so there is always something new to learn helping me enhance my skill set and knowledge.

What do you think is your biggest achievement in your work life?

I don’t really have one. I like to have rolling goals to keep me motivated. I tend to achieve a goal, pat myself on the back and move on to the next one. At risk of yet another cliché, I just want to be good at what I do and continue to develop.

What aspects of this field are the most difficult to deal with?

Challenges come from peoples understanding of the Human Factors discipline, which can be quite a significant barrier. For starters, the term Human Factors does make it seem to be about people, perhaps fuelling the misconception that Human Factors and human error or behaviour are one and the same. There is a lot to get your head around, so confusion or lack of understanding can easily be forgiven. There is a lot of complexity in Human Factors as many aspects feed into this term: cognitive ergonomics, physical ergonomics and organisational ergonomics to name three broad topics. There is a book by R.S. Bridger about human factors in investigation where he says, right from the outset, “Human Factors is not about people, it’s about the things that affect people”. I think that is a great summary of the discipline.

You are a lead investigator: which are the main aspects of an investigation that are less obvious in an undesired event?

When an incident occurs, it is very easy to identify the immediate cause, it is usually a behaviour. The obvious things are physical interactions, or the agent of harm, these are often the focus – i.e., changing signage, changing design etc… These are important, however, what we don’t do so well is explore the decision-making process, consider what that person thought to be true at the time and we don’t consider the influences of the social environment and behaviour of others and how this influences motivation or attitudes. This does take a shift in mindset, understanding the context from the perspective of those involved.

I won’t pretend that I always thought this way, it took some effort to understand it and change my own attitude. It is something I feel is vital to understand though. I mean if our number one asset is people, maybe we should understand what makes them tick. Just as we know the failure modes of a technical system and what to do if it were to deviate from the plan, we should know the same of people and reduce the risk of human failure. That can be done through effective investigations which consider humans and their limitations.

How do you manage to keep a healthy work balance?

I feel like a walking cliché here, but my family. I truly value family time. It is easy to get sucked into work, doing a few extra hours here and there is fine, but it’s important to have a work/life balance.

What are your recommendations to someone starting a career in Human Factors ?

Firstly, I would try and get a good understanding of human behaviour as well as the technical aspects associated with the industry you are working in. This would be true for those coming from a psychology background or an engineering one.

The Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors (CIEHF) have their competence pathway. It sets you off on a journey which spans the Human Factors discipline and by listening to their Webinars and other events you will enhance your knowledge and skill set. I would encourage to join and attend as much as you can. They offer access to Ergonomics and Applied Ergonomics journals, allowing you an insight into recent research and advancements in the discipline. Also, their mentor program is fantastic. They set you up with a Chartered Ergonomics organisation who supports your Human factors journey. Speaking from experience, having a mentot is fantastic and has some great advice and he has supported me for nearly two years. His support has been invaluable.

Interview and pictures by Paola Usala

by Jana Mihulkova

Throughout 2022, IHF has delivered many projects of various scopes and across multiple industries. The experience that our consultants have built on includes but is not limited to rail & transport, construction, defence, nuclear, marine, utilities & facilities, COMAH, and oil & gas. Interestingly, no matter what the primary focus of a project was, one particular topic came up, either directly or indirectly. Fatigue has been repeatedly shown to be an issue within different industries, especially those with frequent on-call work or shift systems.

Fatigue is the experience of extreme tiredness or exhaustion that usually arises from excessive working time, poorly designed shift patterns, or the nature of a task e.g., whether it is machine-paced, complex, or monotonous which makes the workforce more easily fatigued (HSE: Human Factors: Fatigue, 2021).

The effects of fatigue are wide-ranging and, because of the decline in mental and physical performance, they often lead to slower reactions, reduced ability to process information, lapses in memory, absent-mindedness, decreased awareness, lack of attention, underestimation of risk, and reduced coordination.

The importance of fatigue cannot be underestimated as it has been observed that a high occurrence of accidents and injuries occur on night shifts, after a successive number of shifts, or long shifts without sufficient breaks. Also, fatigue has been found to be a contributory factor or a root cause of many major accidents including the Chernobyl, Clapham Junction, Herald of Free Enterprise, and Texas City (HSE: Human Factors: Fatigue, 2021).

IHF Involvement in Fatigue Work

Given that fatigue as a hazard arose so frequently, it is no surprise that IHF has delivered a lot of work on fatigue and fatigue management throughout this year. However, in addition to that, our team conducted an interesting piece of research that assessed fatigue and swing shift patterns, which is one of the most discussed shift patterns in regard to health & safety, within the oil and gas industry.

On swing shifts, workers operate on night shifts for the first week and roll over straight to day shifts for the second week. This shift pattern requires an immediate adaptation to a different schedule hence the wake-sleep cycle without any rest in between. In the HSE study (RR318, 2005), swing shifts showed the highest total desynchrony load[1] compared to other shift patterns (7Days7Nights/14Days/14Nights). It was also found that most subjects adapted to the night shift, however, that was on the 7th day through the tour and did not manage to re-adapt back to dayshifts. Such findings suggested that the workforce was ‘out-of-synch’ with their work and sleep schedule throughout most of their tour.

Our team appreciates the complexity of fatigue, sleep health, and their implications to workers’ performance and health and safety. As a result, IHF conducted a study that not only looked at fatigue levels but also considered sleep hygiene and sleep health that effectively impacted energy levels. Other contextual elements were considered too and captured in a variety of ways. Analysed data were compared across shift conditions to evaluate the risks and impacts of swing shift pattern.

In this study, contributing factors were identified, and this study helped understand the risks tied to the swing shift pattern as well as the sleep health of offshore workers and other challenges workers face. Thanks to this study, IHF set out bespoke recommendations for interventions inclusive of safe shift patterns and effective fatigue management within organisations.

Fatigue is a dangerous, often a silent hazard that should never be taken lightly. It is a hazard that is not particularly obvious and so it can be even more difficult to manage and monitor it effectively. Employers should take the time to understand the impact of fatigue in their workplaces and put practices in place to address this, including fatigue management and relevant risk management. Specialised advice and support are encouraged so you are empowered to tackle fatigue within your organisation with the right tools and knowledge.

Update on 13 December 2022: you can find the original paper at the bottom of this page.

[1] Means the “cumulative hours desynchronised from day-time normal phase or fully adapted night shift”, being “an indicator of the disruption that the schedule causes to the circadian system over the tour duration” (HSE, 2005, p. 15)

References

HSE, Human Factors: Fatigue (2021): https://www.hse.gov.uk/humanfactors/topics/fatigue.htm#:~:text=The%20legal%20duty%20is%20on,manage%20the%20risks%20of%20fatigue

HSE RR318 – Effect of shift schedule on offshore shiftworkers’ circadian rhythms and health: https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrhtm/rr318.htm#:~:text=Night%2Dshift%20work%20causes%20desynchronisation,detrimental%20to%20health%20and%20safety.

[3d-flip-book mode=”fullscreen” id=”14935″][/3d-flip-book]

The HSE figures for Workplace fatal injuries in Great Britain 2021/22 counted a total of 123 fatalities at workplace, over 441,000 reports of non-fatal injuries at work, and 102,000 of those being absent from their workplace for more than 7 days with a substantial cost for the companies impacted. Even though there has been a slight decrease in the accident rate, we see serious accidents happening routinely, and it is crucial for companies to respond to accidents and incidents effectively, with an in-depth investigation that enables understanding and learning. In fact, each incident should be considered as a learning opportunity to discover the true underlying causes of the adverse event and learn from them, rather than attribute blame.

What is an incident and accident investigation?

An incident (and accident) investigation, as HSE states[1], is a powerful ‘retrospective tool’ to increase control over hazards in a working environment, and to report, track and implement change in response to the incident. The investigation consists of an official, structured and in-depth examination about the adverse event beginning with gathering of information on equipment, procedures and the event in question. This process, after the collation and analysis of information, involves a number of stakeholders, not just the people present at the time of the event. The main objective is not only to establish what happened during the adverse event, but also what allowed it to happen.

[1] EI, Guidance on Investigating and Analysing Human and Organisational Factors Aspect of Accident and Incidents

Why human factors are vital considerations in incident investigations.

Investigation concluding that human error was the sole cause of an incident are not acceptable. There are many underlying causes that can create a working environment where humans errors are unavoidable and that are direct consequences of active failures or latent conditions such as inadequate training, poor equipment design, noisy and undesirable working conditions, inadequate work planning or poor safety culture just to name a few. These causes have a considerable impact on workers and could lead to a human failure.

An introduction to Cognitive Origins Analysis an SUPPA model.

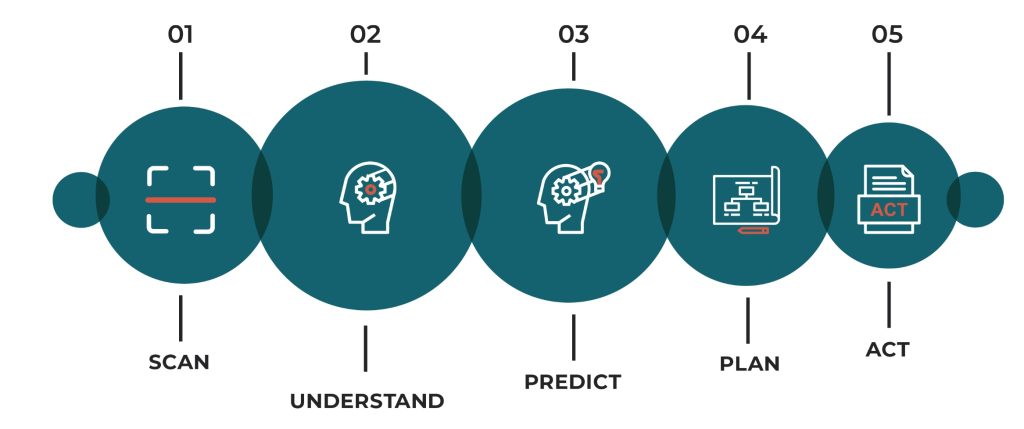

All human performance and interactions with systems come down to our human biology and so, every human failure traces back to the cognitive origins including mental processes of perception, memory, judgment, and reasoning. To understand human behaviour, we analyse these cognitive origins by using SUPPA model: Scan – Understand – Predict – Plan – Act, a dynamic process that completes the investigation of contextual, external, and essentially internally causes of failure.

Be prepared.

It is required by law that businesses carry out incident investigations and review risk assessments after incidents happen, and to fulfil that and act promptly, it is important to be prepared for such events.

A specific skillset and expert knowledge underline an effective investigation. Organisations should have selected competent investigators are ready to act. Whenever in doubt, seek professional advice from a chartered consulting company that will secure a high-standard investigation process for your organisation. IHF specialises in incident investigation and provides a software as a service equipping client to build their own in-house competency.

We are running a webinar entitled “Human Factors Guide to Incident Investigation” where you can learn more about the best practices in incident investigations and practical guidance on applying human factors in investigations.

Work as Imagined vs Work as Done

When we look at approaches to safety and Human Factors, it’s very important to understand the difference between the two terms. For example, one of the leading causes of medical errors is the difference between the way work is imagined and the way it is actually done. It’s very rare that someone sets out to do harm, often they are unaware that they are making a lethal error. The most common example is when management in an organisation thinks a procedure is being completed in a particular way but in reality, the workforce has a different way of completing the procedure. The procedure does not get updated or checked, errors can creep in, or key skills developed to complete work as done can be lost with the skills gap and retirement. In the gap between work as imagined and work as done lies danger.

Work-as-imagined (WAI)

Work-as-imagined (WAI) refers to the various assumptions, explicit or implicit, that people have about how their or others’ work should be done.

Work-as-done (WAD)

Work-as-done (WAD) refers to how something is actually done, either in a specific case or routinely.

Mind the Gap

There is often a considerable difference between what people are assumed or expected to do and what they actually do. In hazardous industries, standard operating procedures (SOPs) may have built up or been adapted over time. Procedures can be complex and lengthy. These processes may have failed to adapt or innovate over time.

Workers may not follow standard operating procedures when:

- The procedure fails to align with what they were taught in training

- Workers may think that their method of performing the task is better than the method used in the procedure. This can happen when a worker has decades of experience working in an industry and in their mind has found the “best” way of doing things.

- The procedure makes the task more complex and difficult to complete

- The procedure is unclear, leading to misinterpretation of the steps required to complete the task

- Workers work from memory rather than referring to the procedure. This can be a particular issue if the task is particularly repetitive.

- Leaders do not clearly articulate that they expect the procedures to be followed and fail to check if the procedure is being followed correctly.

- Staffing levels are sub-optimal leading to staff cutting corners.

The Solution

Examining WAI and WAD is an important part of conducting Hierarchical Task Analysis (HTA) as part of an SCTA. Where there is a gap between WAI vs WAD, leaders need to dig deeper to understand, and then take appropriate actions to resolve the gap. Observing how a procedure is carried out in the field can give a better understanding of the risk of the task and help reduce the likelihood of failure. If this observation is carried out with different people and in different environments, this may fill in some of the gaps in how the work is done. To get the clearest picture interviewing workers can be used in tandem with observations.

IHF helps for a range of high risk industries including aviation, chemical processing, COMAH sites, financial services, health, nuclear, oil & gas and pharmaceutical conduct SCTA’s. Our training courses (approved by the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors) and software solutions help organisations build their own in-house capabilities, with our consultants on hand to guide our clients on best practices. Having this SCTA knowledge in the workforce also exerts a positive influence on the quality of risk assessment and incident investigations and also the quality of improvement suggestions. IHF can help organisations streamline their SCTA processes, standardise the processes across the organisation and bring all their information into one easily accessible portal.

To learn more Contact Us.

Human Error v Human Factors

Often the terms human error and human factors are used in an interchangeable way – but they are quite different things.

Human error refers to an unintentional action or decision which can then have a knock-on consequence such as an accident or workplace incident. Or put more simply it involves all those instances where a planned activity fails to achieve its intended outcome.

Human Factors on the other hand delves much deeper. It accounts for why the mistake was made. So human factors look at the reasons why the errors occur. So, when we address the human factors in relation to health and safety, the aim is to optimise the human performance and reduce the human failures.

The danger is if you focus your workforce safety around human error, then you miss the why. By looking at it from a human error alone you will miss something that has built up over time.

Safety is not about who failed it’s about what failed

The easiest excuse after a safety incident is to blame someone or finger point. Instead, organisations which pride themselves on safety should dig deeper, explore their strategies, systems, and the environment. A worker’s behaviour or action often contributes to an incident but it’s often not the main cause. It should be viewed as a warning or symptom that there are problems in the organisational system and the environment. So human factors can find the issues that may be hidden below the surface.

A bad system will beat a good person every time

As Edwards Deming (one of the Founding Fathers of Total Quality Management) said: “A bad system will beat a good person every time.” An employee in the most part does not set out to cause an incident and will have good intentions when going about their duties. If you have a no blame culture, then workers will tell you their challenges and report incidents such as near misses. Attributing safety challenges to a lack of situational awareness does little to improve the situation. Organisations need to allow people to perform at their best by ensuring they are not afraid to express their concerns.

If we look at an iceberg what we see does not give us the full picture with as much as 90% can be contained below the surface, out of site. So an incident could be a sign of a much larger problem. Businesses must therefore consider safety incidents as early warnings of something bigger that could happen in the future.

Employees won’t tell you when they are tired. Several studies have shown that employees won’t discuss fatigue in the workplace. In one survey by Westfield Health 86% of workers said they don’t feel confident speaking with their line manager about fatigue.

The effects of fatigue are wide ranging and include, making errors, a decline in mental and/or physical performance with some even falling asleep while driving. Fatigue results in slower reactions, reduced ability to process information, memory lapses, absent-mindedness, decreased awareness, lack of attention, underestimation of risk and reduced coordination.

This has huge dangers in high-risk or hazardous industries such as chemicals, renewables, manufacturing, mining, oil and gas, pharmaceutical, transport, and utilities. If you add into the mix lone workers, the impacts can be even more extreme when their colleagues are not there to help them should the worst happen. Fatigue has been a root cause of major accidents eg Herald of Free Enterprise, Chernobyl, Texas City, Clapham Junction.

Integrated Human Factors have been working on a pilot to help monitor driver fatigue in light rail and trams as part of the Driver Innovation Safety Challenge (DISC) project. DISC is being led by Edinburgh Trams with the support of UK Tram and Transport for Edinburgh and a partnership of public and private sector organisations including the City of Edinburgh Council and the Scotland CAN DO Innovation Challenge Fund. The pilot is currently collecting a large quantity of data to “train” the FOCUS+ algorithms through machine learning. The system includes a wearable device worn round the wrist and a hub that can be attached to the wearers belt to monitor tram drivers and give early warning if they fall asleep, black out or lose focus due to fatigue.

Fatigue needs to be managed, like any other hazard. It should not be underestimated and there is often a legal duty on employers to manage the risk of fatigue.

A fatigue risk assessment could include the use of tools such as HSE’s ‘fatigue risk index’ which looks at issues such the impact of working hours and shift patterns on fatigue.

So, as employers we should not rely on the workers to tell us they are fatigued but start to identify the factors that can lead to the onset of fatigue in their workforce. Or they may wish to go a step further by using health-monitoring tech to improve safety for their workforce and customers.

There is a huge pressure in change initiatives to be completed quickly often without considering the human element in enough detail.

Organisations often don’t consider the human contribution early enough and in enough detail. There can be a huge difference between a project that is overly technically focussed, with little regard for the people who need to enact the technical processes or maintain the processes of the project and projects that have embraced the human element from the beginning and maintain this focus throughout the project.

We recommend that organisations take small and frequent human considerations into account right the way through a change initiative.

The difference between something that’s technically accurate and something that’s fit for purpose

If we look at designing a kettle, we could develop a kettle that functionally works proficiently by boiling water and doing the job it was intended to do. But as we are likely to use this product daily, if a kettle was designed with a handle that loosened off over time, this would increase the risk of burns or scalds.

This same logic could be applied to a management of change project that hasn’t gone to plan as they have almost exclusively focussed on what they are trying to do technically without embracing how people will interact with the project. In the kettle example, there have been large customer safety recalls by Whirlpool where the costs or reimbursing customers were substantial.

Other factors to consider could be how people access the information in a project, understanding what the feedback of the system is giving you.

By integrating human factors into a project, an organisation can make the shift from something that is technically accurate to something that is fit for purpose.

The common sense argument

We often hear in the workplace, even hazardous workplaces that safety is just common sense.

What is common sense to one person is often not common sense to another person as human beings are all different. Common sense is therefore notoriously uncommon.

Common sense is a learned behaviour and changes over time. A young child might conceivably put its hand on steaming water as it hasn’t learned that this action can cause it pain through burns.

If we take a workplace change project the goal therefore shouldn’t be to develop common sense but to seek competence of the new way of doing things. So the focus needs to be on building employee competence.

We can ask ourselves questions like:

- How within a management of change process can people fail?

- Where do we know they have failed in the past?

- How do they fail?

- What can we do about it proactively

How can you include human factors in a change management initiative?

We need to actively consider the human contribution from the start to the finish. We need to understand more deeply what the people’s interactions are with colleagues, how they interact with the business digitally and the overall environment of the business. Building a visual model can help organisations understand what technical components exist within the business and how they interact with the human elements. Often, it’s within the interaction where human error creeps in.

When we start to see repetition of failures through human error, we would look to improve upon this sub optimal output. We can then look to improve some key business indicators and monitor key KPI’s set by the organisation over time. Once we see one department in the business improve the same fundamentals can often be applied to improve other parts of a business to build cumulative value.

By performing business-critical task analysis we can identify and prioritise where the human contribution lies and what the risk is associated with that. If a project fails, we could perform a human factors investigation to find out how the human contribution contributed to the “why” of what failed.