How to conduct an incident investigation

In Europe, every year over 40 million working days are lost through work-related injuries and ill health, at a cost to business of £2.5 billion. (1)

It’s particularly distressing when an injury happens more than once at the same company, indicating that lessons aren’t being learnt. Responding to accidents is at the heart of preventing them from repeating, so it’s crucial to identify what went wrong and take reformative steps – this is the core principle of an incident investigation.

What is an incident investigation?

Incident investigation is a process for reporting, tracking, and implementing change in response to workplace accidents.

An effective investigation requires a methodical, structured approach which begins with information gathering on equipment, procedures and the event in question. Input is expected from a number of stakeholders, not only the ones present when the incident occurred. Once there’s sufficient information, analysis of the failings which led to the incident can take place. The findings will form the basis of an action plan to prevent the accident from happening again and for improving your overall management of risk.

Which events should be investigated?

Not all incidents merit a full incident investigation – the decision it partly down to the HSE managers judgement. Weight should be given to the consequences (or potential consequences) of the incident and the likelihood of it happening again.

Who should carry out the investigation?

For an investigation to be worthwhile, it is essential that the management and the workforce are fully involved. Depending on the level of the investigation (and the size of the business), supervisors, line managers, health and safety professionals, union safety representatives, employee representatives and senior management/ directors may all be involved. As well as being a legal duty, it has been found that where there is full cooperation and consultation with union representatives and employees, the number of accidents is half that of workplaces where there is no such employee involvement.

How most companies do it in practice?

When investigating an incident, companies usually use a pen and paper during data collection to make note of all relevant details, this information is then typically analysed using post-it notes in an office to drill down to the root cause of an incident. The 5 why method will often be used with a heavy focus on the materials and process side of things. Unfortunately, in these cases there is often only a nod towards the Human Factors causal factors, which means key factors that lead to the incident may be missed, not addressed and lead to a recurrence of the incident.

Frequently, those conducting the analysis of the incident are not fully acquainted with the full range of human factors elements which may have contributed to the incident, and in some cases are not from the company itself but from external organisations sometimes based a distance away from the company where the incident occurred.

The problem with these approaches is that aspects of the incident may be missed in the post-it note investigation, and these notes will require electronic capture once the investigation has been complete. This adds to the workload of those carrying out the investigation and increases the possibility of information being lost due to lost or miss placed post-it notes. Although steps may be taken to ensure a systematic analysis of the different aspects of the incident, parts of the process may be missed or not analysed as deeply as they could be as there is a reliance on memory of what should be reviewed when it comes to assessing the contributing human factors elements. Where external individuals have been brought in to conduct the investigation and analysis, they may lack the local knowledge and insight required to fully understand what went wrong.

Why HF-AIR offers the best approach

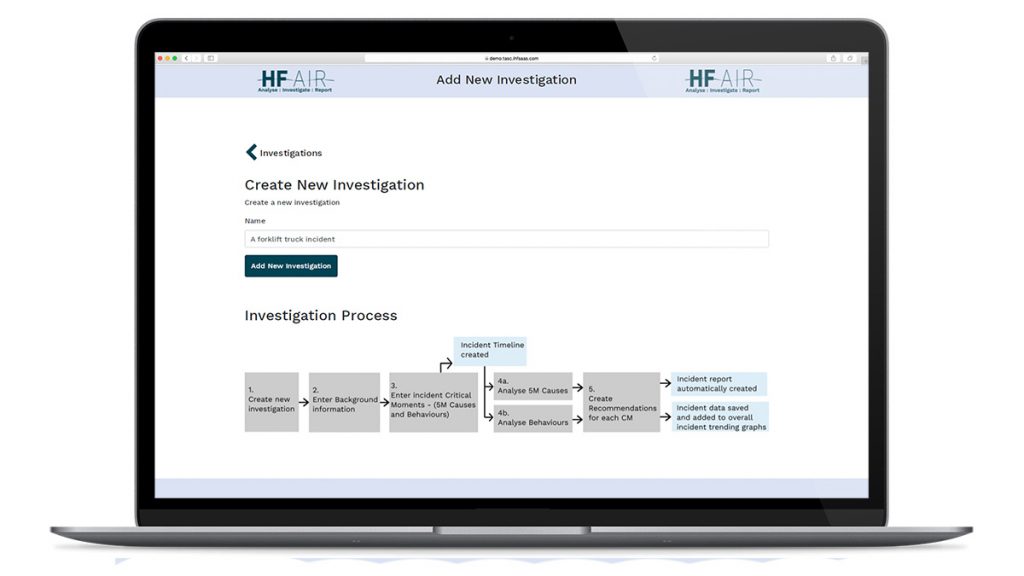

HF-AIR™ is a complete online incident investigation system. The integrated analysis tools allows you to investigate technical failures and human errors then save your reports all in one place.

The tool is designed to provide you with an online application that enables the easy input of the timeline of an incident, which includes in depth cognitive behaviour and 5-M (Machinery, Methods, Materials, Mother nature and measurement) causal analysis. These analysis tools allow you to focus on each critical step of the incident, drill down to the contributing factors, including those associated with the individual and the organisation, and develop a clear understanding of why the incident occurred. This makes it easier to identify recommendations for improvement to ensure that the incident, or one like it, does not occur again.

Once the analysis has been completed and recommendations have been identified, this information can be easily downloaded within the format of a report that captures all of the information provided in a well laid out, easy to read word format. This structure can be tailored to your organisation to ensure that it fits your reporting structure and styling. Furthermore, the intention with this software is to train your employees to use it, this provides them with ownership and a developed understanding of what leads to and may cause an incident.

Our software also provides you with the ability to conduct a top-level analysis of all of the investigations conducted within your company. It provides you with the opportunity to identify across the different incident types what proportion of critical moment types have occurred, and the type of cognitive and 5M causes have been more likely to occur. Furthermore, our tool provides a central space for all documents including incident records and interview notes. This enables easy access of information for reference and auditing purposes at a later date and ensures that no information is lost with staff changes.

If you’re interested in a demo of HF-AIR then please get in touch

References

1 European Social Statistics: Labour Force Survey Results 2001 ISBN 9289436050

Facebook & Instagram outage likely caused by human error

Yesterday at around 4.30pm Facebook, Whatsapp and Instagram all suffered outages, meaning more than 3 billion users could no longer access their accounts. Rumour has it, it was caused by human error. Here’s CTO of Facebook Mike Schroepfer announcing the disruption:

*Sincere* apologies to everyone impacted by outages of Facebook powered services right now. We are experiencing networking issues and teams are working as fast as possible to debug and restore as fast as possible

— Mike Schroepfer (@schrep) October 4, 2021

In a lengthy statement, Facebook blamed the disruption on a “faulty configuration change”. It seems users were not being directed to the correct place by the Domain Name System (DNS) – something controlled by Facebook. This has led most analysts to conclude that human error, or more likely a sequence of errors, led to the outage.

Facebook said in a statement: “Our engineering teams have learned that configuration changes on the backbone routers that coordinate network traffic between our data centres caused issues that interrupted this communication.

“This disruption to network traffic had a cascading effect on the way our data centres communicate, bringing our services to a halt.”

Cloudflare, a DNS provider, shed further light on Twitter saying five minutes before the outage, it saw a series of updates to Facebook’s book services. This indicates that the updates inadvertently led to the outage.

How can this be prevented from happening?

Facebook will no doubt have proper procedures in place to mitigate mistakes. It will certainly use version control and have an approval process for changes to the DNS. What it may not have prepared for, was all these failing due to poor decision-making. To solve this, they should look at it through the lens of human factors.

If your business has experienced technical human errors, IHF can help. Get in touch to learn more

How human error cost Max Verstappen the Italian Grand Prix

Back in September, the Italian Grand Prix took place against the backdrop of a simmering rivalry between Lewis Hamilton and Max Verstappen. In dramatic fashion, the two crashed on lap 26, ending the race for both drivers and nearly causing serious injury to Hamilton. Now, it’s easy to blame Verstappen’s overly aggressive driving for the crash, but taking a human factors perspective, that’s just not correct. We need to look at the extreme performance influencing factors and exceptional circumstances of the race – we’ll use the 5M-analysis model.

5M-Cause Analysis

A 5M-Cause analysis refers to any influencing factors which are not related to a person’s behaviour (Machinery; Methods; Materials; Mother-nature; Measurement). Let’s start by looking at the changes introduced by the FIA (F1’s governing body) to make pitstops safer.

On September 1st the FIA brought in a new technical directive, TD22A, to help reduce the risk of cars leaving their pit box too soon or without their wheels properly attached. This happened in 2018’s F1 season, resulting in serious injury to a Ferrari mechanic. The practical implications of the new directive is that mechanics have to wait for a signal light to illuminate before the car is released (within 5M, this would be machinery).

Before the directive came into force, every F1 team had time to train their mechanics and implement a the new procedure, but the Italian Grand Prix showed that Red Bull hadn’t quite nailed it. Red Bull took 11 seconds to complete Verstappen’s first pit stop which was, without a doubt, a factor behind the crash with Hamilton. You could argue that the 11-second pit stop was the main factor leading to the cognitive process failure i.e. the driving which led to the crash.

Red Bull’s Team Principal, Christian Horner, put the mistakes down to human error, which in the context of Human Factors, is correct but we thikn

Why Red Bull is like any other UK business

The error made by Team Red Bull has parallels with many of the transformations UK companies are going through. Adoption of new technologies, pressure to increase supply chain transparency and the movement towards more efficient (and eco-friendly) systems are just a few of the driving forces behind corporate modernisation. While staff can be trained and procedures can be drawn up, errors are still possible, and in some cases should be expected.

This is why it’s important to take an employee-first perspective. You must understand both the conscious and subconscious behaviours of your employees to know exactly how safe any new workplace practices, procedures or systems are.

That’s where IHF comes in. We’re experts in investigating and analysing human risk using established human factors models. We have clients in a broad range of industries from COMAH and Oil & Gas to Aviation and Construction.

If your company has critical procedures which must be consistently followed, or systems that are complex but must be operated properly, then human factors can help.

Get in touch with IHF today.

What are the root causes of human error?

While every workplace is unique, human errors happen at all them. They can never be eliminated, but they can be minimised. Research into the Oil and Gas industry has found that most human errors can be attributed to 1 of 3 categories. They are:

- Process and procedure non-compliance

- Lack of safety culture adherence

- Breakdowns in safety critical communications

Understanding these 3 categories is a key step to addressing human error, the next step is knowing how to address them.

Historically, in the Oil and Gas industry, human errors haven’t been dealt with in a ‘human factors-friendly’ way e.g. the employee has been blamed and disciplined. Often the solution is to instead address the overarching root causes (Gordon, 1998; Sanders, 1987; Wickens, 2004).

How can Human factors help? It allows for a holistic approach to non-technical error. Our expertise highlights operator behaviours and limitations such as stress and strain, fatigue, cognitive load, communications, distractions, attention focus, situation awareness and other critical variables required to maintain operational safety. Addressing these previously disregarded factors allows for a user-centred approach when re-designing processes and procedures to consider the capabilities and limitations of the human tasked with following the instructions (Endsley, 1995; Hancock & Parasuraman, 2002; HSE, 2012).

Clear communication is critical

To take the example of communications: IHF reviews safety-critical communications frequently – highlighting instructions which are difficult and confusing to follow, do not represent a logical order, are located over multiple documents, out-dated and do not clearly reflect the current operational standards for ‘doing things’ (Thomas & Carroll, 1981; Reason, 1995).

Deconstructing and rebuilding procedures

Rebuilding procedures from the perspective of the end-user allows for human factors to be taken into account. Information can be ordered in a manner which accurately represents the task steps within the procedure, dangers and hazards can be highlighted as initial, critical information and instructions can be worded, presented and broken down in a manner which will not ‘overload’ the end-user (HSE, Shackel, B, 1991; HSE, 2012).

Summary

While this is a brief example discussing just a few human factors components and applications, it serves to highlight the necessity of the field as a tool to manage operational safety, human-error and accident/near miss occurrence. A human factors approach should be taken no less seriously than the physical integrity of workplace tools and equipment.

References

Endsley, M. R. (1995). Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 37(1), 32-64

Gordon, R. P. (1998). The contribution of human factors to accidents in the offshore oil industry. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 61(1), 95-108.

Hancock, P. A., & Parasuraman, R. (2002). Human factors and ergonomics. Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science.

HSE, (2012). Human factors that lead to non-compliance with standard operating procedures. Health & Safety Laboratory for the HSE.

Wickens, C. D., Gordon, S. E., & Liu, Y. (2004). An introduction to human factors engineering.

Reason, J. (1995). Understanding adverse events: human factors. Quality in health care, 4(2), 80-89.

Sanders, M. S., & McCormick, E. J. (1987). Human factors in engineering and design . McGRAW-HILL book company.

Shackel, B. (1991). Usability-context, framework, definition, design and evaluation. Human factors for informatics usability, 21-37.

Thomas, J. C., & Carroll, J. M. (1981). Human factors in communication. IBM Systems Journal, 20(2), 237-263.

Understanding Human Factors in Procedural Compliance

Recent human factors legislation focuses on procedural compliance as an integral aspect of operational safety.

Human factors: the consideration for individual human characteristics, environment, organisation and job elements provides a robust framework for understanding work behaviours.

Are your written procedures up to scratch?

Compliance is underpinned by the extent to which organisations are able to influence the behaviour of their employees. The most common example of this is through the presentation, positioning, wording and layout of safety critical information, processes, procedures, tasks and task steps.

In theory, having a clear set of instructions to follow should allow a task to be completed rapidly, adequately and in accordance with agreed safety standards. In particular written procedures relating to operation and maintenance are vital to ensuring workflow consistency. Procedures should embody a standardised level of base-line knowledge and represent the best practice for task completion (Gordon, 1998; Hancock & Parasuraman, 2002; HSE, 2012).

The link between non-compliance and risk

While adherence to correct procedures plays a vital role in promoting consistency of task outcomes, safety culture integrity and operational success, poorly written procedures are an often-cited reason for non-compliance and deviation from recommended actions. Investigation of major accidents and incidents within the energy sector has attributed non-compliance as a causal factor to increasing risk vulnerability (Allnutt, 1987; HSE, 2012; Wickens, 2004).

When a worker intentionally deviates from standard procedural instructions this is considered procedural violation. The definition does not imply that the end-user was aware of the negative consequences or that the end result was intentional, simply that somewhere in the task trajectory a non-compliance choice was made (HSE, 2012).

Driving behavioural change

One of the major areas we specialise in is a behavioural approach to procedural risk. Oil & Gas clients striving to enhance procedural compliance often look to our I3 consultancy service to review existing process for non-compliance risks.

Our subject matter experts are highly experienced in rebuilding existing procedures from the ground up in order to facilitate compliance and adherence. Considering the end-user from the earliest stage in the process development cycle, while also maintaining operational end goals is vital for the successful integration of human factors.

Guidelines for Procedural Creation The wheel below highlights some of IHF’s recommendations for revising, designing and publishing robust and reliable procedures, which accurately represent task completion.

References

Allnutt, M. F. (1987). Human factors in accidents. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 59(7), 856-864.

Gordon, R. P. (1998). The contribution of human factors to accidents in the offshore oil industry. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 61(1), 95-108.

Hancock, P. A., & Parasuraman, R. (2002). Human factors and ergonomics. Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science.

HSE, (2012). Human factors that lead to non-compliance with standard operating procedures. Health & Safety Laboratory for the HSE.

Wickens, C. D., Gordon, S. E., & Liu, Y. (2004). An introduction to human factors engineering.

What is a toolbox talk?

A toolbox talk is an informal team meeting held to address a health and safety issue. It can be about anything safety-related from a workplace hazard to a quick refresher on proper tool use. It may be used to highlight a particular worker’s conduct without calling him out; for example the crew supervisor (who runs the meeting) will remind ‘everyone’ to leave the guards in place when using dangerous tools.

Why are they useful?

Running a successful toolbox talks can save lives.

They’re considered best practice for a number of high-risk industries, including offshore energy and healthcare, to identify safety problems at an early stage. They encourage open dialogue and tackle safety issues in a fast and simple way. Employees also feel listened to, leading to improved job satisfaction.

From a regulatory standpoint, they help companies comply with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). This was put in place to ensure companies look out for their employees’ wellbeing.

The effectiveness of toolbox meetings is backed up by research. In one study, they were found to reduce workplace incidents by 82%, as opposed to monthly safety talks (Associated Builders and Contractors in 2020).

However, they’re not always carried out in the most effective manner. The idea is to keep them short and to the point, with clear actions at the end of the meeting. However, they often become talking shops and debates, without clear outcomes.

How to do them properly

Here are five fundamentals every toolbox talk should have.

Brevity

Safety in working environments such as oil rigs and hospitals is of paramount importance. However, that shouldn’t equate to toolbox talks taking hours to deliver. It’s advisable to hold smaller talks more regularly rather than overload people with information over a period of hours in just one session.

An effective toolbox talk should be around 10-15 minutes long and an interactive meeting between the supervisor and staff. While the detail of the talk is important, it’s also vital that everyone has their chance to air their views and feel like they’re being listened to.

Authority

While toolbox talks are meant to be informal, it’s critically important they’re conducted by someone in a position of authority. Occasional toolbox talks just held between staff doing the job could bypass a number of safety concerns as well as not being properly recorded or reported.

When toolbox talks are held regularly by a supervisor, it gives staff the chance to air their concerns and ideas and ensures these are reported further up the chain to management if necessary.

Relevance

Toolbox talks aren’t the place for general safety presentations. Toolbox talks should be held in the working environment rather than a formal training area and focus on specific tasks or procedures relevant to staff.

The language used should be what the staff understand and not ‘management speak’ that leaves any room for confusion or misunderstandings. For example, talking about safety-inspired changes to a particular procedure may fall on deaf ears if the team members actually already perform it in a different way from the official guidelines.

Clarity

At the start of a toolbox talk, it should be made clear what the topic is going to be. If these briefings are allowed to grow arms and legs, the result could be a confusing and lengthy meeting. When people aren’t engaged in toolbox talks, the safety of everyone in that environment can be put at risk.

Typically each toolbox talk will cover just one safety topic for discussion to keep things clear and simple for everyone. The way the information is delivered by the supervisor is another important consideration and any one to one discussions that need to take place should be done so away from the group.

Accountability

Every toolbox talk should be recorded by the supervisor or manager who’s given the talk. It’s important to have a clear and up-to-date record of what discussions have taken place in terms of operational safety. If no records are kept, different accounts of what was discussed could emerge in the event of an incident.

It’s also important to keep track of which staff were present at each toolbox talk, particularly in a shift working environment such as an oil rig. It only takes one member of a crew to miss out on an important safety briefing for potential safety issues to arise.

Summary

Remember BARCA – Brevity, Authority, Relevance, Clarity and Accountability to ensure your toolbox talks are effective and help keep everyone safe in the workplace.

We’ve created a poster which you can print and stick it on the wall:

Click on the image to view it:

The Bowtie Model is a risk assessment tool which visualises complex risks in a understandable diagram. It allows you to structure your thinking and reveal holes in your risk management