Human Factors consultancy IHF has established a partnership with an innovative duo from the aviation and medical sectors.

Airline captain James Taylor and his consultant oncologist father Roger will work as associates of Edinburgh-based IHF to enhance its capabilities in human factors, and will set up an office in Brighton.

IHF’s team of 24 consultants and trainers around the world set out to understand and resolve what are commonly regarded as “human errors” in any system or process.

Apart from big oil and gas, trade unions are also signed up as they make risk and safety a top priority for their members in these industries.

Neil Clark, CEO, who runs IHF said: “I am really excited about partnering with James and Roger. Its testament to how far IHF have come in the last 12 years that we are bringing on board such high calibre professionals.

“Human Factors is a growing discipline in both the healthcare and aviation sectors, so it makes sense to bolster our teams’ capabilities in these areas. As an RAF pilot myself I have seen how best practice in aviation is being adopted by other sectors and the influence of human factors continues to grow exponentially in medicine”.

James Taylor has 16 years experience as an airline pilot with seven of those as a captain. He has also undertaken the training of pilots in the flight simulator.

He said: “Every time I fly a passenger airliner or train a pilot, I am reminded of how important the safety culture in the industry is, with the key focus being on implementing procedures that have human factors at their heart.

“Everyone in the industry acknowledges the importance of the strong safety culture which over the decades has developed robust processes for identifying and correcting issues which may carry even a very slight risk.

“Human factors may pose a risk in themselves or exacerbate the risk from mechanical or electronic factors. I strongly believe that airline style safety can and should be applied to all settings especially in healthcare”.

Roger has been a consultant oncologist for 35 years, planning and supervising radiotherapy and chemotherapy for patients with cancer and contributed to the “Towards Safer Radiotherapy” document.

He has been vice-president of the Royal College of Radiologists and Clinical Director for Swansea Health Board Cancer Services.

He said: “Radiotherapy is already one of the safest processes in hospital medicine, however we need to maintain our guard. Radiotherapy planning and a delivery are multistep processes requiring input from several different staff groups.

“Therefore, it is essential to mitigate the risk from any human factor which might pose a risk to safety. In healthcare circles we often talk about applying the airline industry safety culture but there is much more that could be done to implement this across organisations”.

Building your own Intelligent Customer Capability

The concept of Intelligent Customer (IC) in relation to high-hazard safety was developed by the UK Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) and has gained acceptance around the world.

The UK Health and Safety Executive defines IC as:

“The capability of the organisation to have a clear understanding and knowledge of the product or service being supplied”.

Both safety critical organisations in hazardous sectors as well as large complex organisations will use contractors to help them with various activities. But there is a joint responsibility, so it’s important that organisation understand, oversee, and accept any technical work undertaken by contractors.

Organisations must be able to lead the presentation of the safety arguments to the regulator. This could include having a human factors strategy in place, explaining the process for developing and using safety critical procedures or describing the fatigue management arrangements that are in place.

Questions organisations should ask themselves before engaging with a human factors consultancy?

- Will this engagement help us to build up our own in-house skills through shared learning? It’s important for organisations to consider if they could perform the work themselves if a contractor was no longer around. So, what training and consultancy is required at the start of an engagement to enable an organisation to build its in-house human factors capabilities themselves.

- How competent is the consultancy? Is the consultancy a chartered member of the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors? The HSE mentions that careful consideration should be given to the potential consequences of outsourcing of safety-related work. Companies must take steps to ensure that contractors are competent to carry out health and safety-related work. Companies should seek to retain intelligent customer capability to ensure that they can appropriately manage and oversee the work.

- How can you develop whole-system functionality checks. It’s important to look at all the different safety-critical elements to get a holistic picture. This is especially important where work is contracted out to a range of specialists.

- Are they experienced in your sector? Consultancies that have a track record in sectors such as nuclear, aviation, maritime, oil and gas, pharmaceutical, manufacturing or even financial services will be best placed to meet your sectors needs having built up experience of the specific challenges your type organisation faces.

Organisations who adhere to this guidance and then demonstrate to regulators such as the HSE that they are delivering the ‘intelligent customer’ capability in practice.

IHF software solutions, combined with training and consultancy, enable organisations to manage their facility’s human factors needs in an efficient, consistent, and confident manner. With a streamlined process, standard reports and an intelligent approach to stakeholder engagement, your organisation will continually follow best practice, allowing it to establish and scale up its human factors function quickly, meeting the requirements of the regulator.

To build an in-house capability IHF can help organisations train operators and team leaders. For example, our CIEHF accredited Safety Critical Task Analysis (SCTA) also aims to turn any organisation into ‘intelligent customers’ by raising the in-house capabilities of their human factors focal point to understand, monitor and in some cases deliver components of an SCTA. This means that, for the activities which require an external consultant, the internal staff will know exactly what needs to be delivered on the overall path and can supervise the delivery from the external consultant.

Contact us to discuss how we can help your organisation build ‘intelligent customer’ capability.

There is a huge pressure in change initiatives to be completed quickly often without considering the human element in enough detail.

Organisations often don’t consider the human contribution early enough and in enough detail. There can be a huge difference between a project that is overly technically focussed, with little regard for the people who need to enact the technical processes or maintain the processes of the project and projects that have embraced the human element from the beginning and maintain this focus throughout the project.

We recommend that organisations take small and frequent human considerations into account right the way through a change initiative.

The difference between something that’s technically accurate and something that’s fit for purpose

If we look at designing a kettle, we could develop a kettle that functionally works proficiently by boiling water and doing the job it was intended to do. But as we are likely to use this product daily, if a kettle was designed with a handle that loosened off over time, this would increase the risk of burns or scalds.

This same logic could be applied to a management of change project that hasn’t gone to plan as they have almost exclusively focussed on what they are trying to do technically without embracing how people will interact with the project. In the kettle example, there have been large customer safety recalls by Whirlpool where the costs or reimbursing customers were substantial.

Other factors to consider could be how people access the information in a project, understanding what the feedback of the system is giving you.

By integrating human factors into a project, an organisation can make the shift from something that is technically accurate to something that is fit for purpose.

The common sense argument

We often hear in the workplace, even hazardous workplaces that safety is just common sense.

What is common sense to one person is often not common sense to another person as human beings are all different. Common sense is therefore notoriously uncommon.

Common sense is a learned behaviour and changes over time. A young child might conceivably put its hand on steaming water as it hasn’t learned that this action can cause it pain through burns.

If we take a workplace change project the goal therefore shouldn’t be to develop common sense but to seek competence of the new way of doing things. So the focus needs to be on building employee competence.

We can ask ourselves questions like:

- How within a management of change process can people fail?

- Where do we know they have failed in the past?

- How do they fail?

- What can we do about it proactively

How can you include human factors in a change management initiative?

We need to actively consider the human contribution from the start to the finish. We need to understand more deeply what the people’s interactions are with colleagues, how they interact with the business digitally and the overall environment of the business. Building a visual model can help organisations understand what technical components exist within the business and how they interact with the human elements. Often, it’s within the interaction where human error creeps in.

When we start to see repetition of failures through human error, we would look to improve upon this sub optimal output. We can then look to improve some key business indicators and monitor key KPI’s set by the organisation over time. Once we see one department in the business improve the same fundamentals can often be applied to improve other parts of a business to build cumulative value.

By performing business-critical task analysis we can identify and prioritise where the human contribution lies and what the risk is associated with that. If a project fails, we could perform a human factors investigation to find out how the human contribution contributed to the “why” of what failed.

What is a safety critical task analysis

A safety critical task analysis (SCTA) is a specific form of task analysis that looks at tasks that have potential to be a major accident hazard. It focusses on not just how things may go wrong, but more importantly on how to ensure that these tasks are carried out correctly when called for.

Who carries out SCTAs?

SCTAs tend to come in all shapes and sizes. This is in part because of the range of sectors which use them; oil and gas, chemical processing, nuclear and aviation to name but a few. The personnel aren’t uniform either; they might be done by human factors consultants, HSE managers, process safety engineers, operations managers or someone chosen ad hoc because they seem like the the right person.

The SCTA process and reporting format varies greatly too. We’ve even seen organisations who have several SCTA processes across different sites. Though, more often than not, SCTAs are conducted using generic software such as Excel, Word and the like.

The problem with Excel SCTAs

Whilst it may seem like generic office software achieves the desired results, there are a multitude of potential failures – IHF has previously encountered a company which was working on two versions of the same task analysis, because one was saving to their desktop and the other was saving to the cloud.

On another occasion, a company was asked to produce its safety critical task analyses in advance of an HSE inspection. The company was using word documents, spreadsheets and diagrams so each SCTA had many files, but the company hadn’t kept the files organised. It took an unnecessarily large amount time to piece them all together before sending to HSE.

These apparent issues with carrying out SCTAs can sometimes encourage organisations to attempt to use less rigorous methods of assessing risk. For example a British Airways aircraft was returned to service in 2004 in an unsafe state. Specifically, an access panel was missing from a fuel tank after it was removed to improve lighting. Effective SCTA would have identified the lack of light as a potential issue, and recommended mitigations that could have prevented the incident. Again, nobody was hurt on this occasion, but the aircraft in question lost at least 37 tonnes (around 45000 litres) of fuel through a combination of fuel lost to the leak and fuel that was required to be jettisoned, along with the not inconsiderable costs associated with cancellation of the flight, and the much harder to calculate cost of reputational damage.

How do to a STCA with TASC?

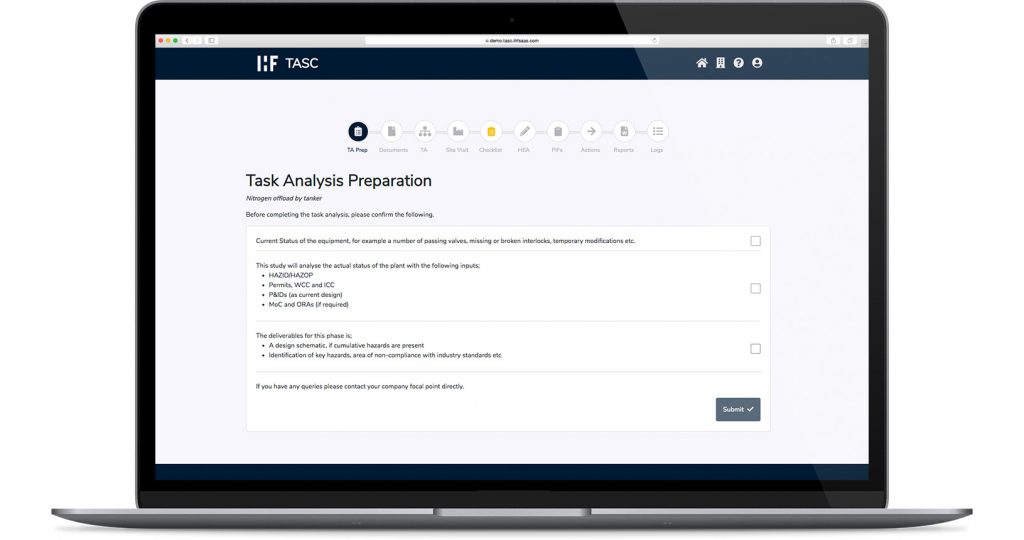

IHF’s software, TASC, addresses all of these problems and more. It’s clear, user-friendly interface is designed to walk users through the SCTA process in its entirety, with powerful tools used to carry out task screening to ensure that time is not wasted carrying out analysis of tasks that carry only minimal risk.It’s task analysis feature helps to ensure that the tasks is broken down into appropriate steps, and allows organisations to gain an understanding not just of how tasks should be carried out, but much more usefully, how they are carried out. This has many benefits – other than the obvious potential benefit in risk reduction, it can also help to identify effective and safe user knowledge that can be shared organisation wide, reducing costs and increasing productivity.

Most importantly of all however, its Human Error Analysis tool is designed in such a way as to allow all potential human errors associated with each subtask to be identified, along with additional factors that may increase – or decrease – the likelihood of the failure. It allows users to identify safeguards that can be put in place, along with mitigations that can be used to improve the outcome should the worst happen. It does all this in a clean, streamlined manner aligned with guidance from both the HSE and the Energy Institute – helping to improve audit outcomes in the process.

If you’re interested in a demo of TASC then please get in touch